Image Credit: Malcolm Southwood

Mineral Species

Leadhillite

Type Locality

No

Composition

Pb4(SO4)(CO3)2(OH)2

Crystal System

Monoclinic

Status at Tsumeb

Confirmed

Abundance

Somewhat rare

Distribution

First and second oxidation zones

Paragenesis

Supergene

Entry Number

Species; TSNB207

General Notes

Leadhillite is very much rarer than either anglesite or cerussite, reflecting its relatively narrow Eh/pH stability range between these two minerals which is also highly dependent on pCO2 and the activity of other dissolved species (Williams 1990).

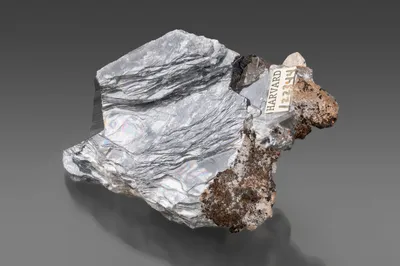

Leadhillite seems to have attracted relatively little attention in the early Tsumeb-related literature (pre-1970s), yet fine specimens from the first oxidation zone had been known for at least forty years. The Karabacek Collection at Harvard University, for example, includes a 75 mm partial crystal of leadhillite (MGMH 93920) that was acquired pre-1935. Palache et al. (1951) note the occurrence of "fine crystals" of leadhillite from Tsumeb. Yet for reasons unknown there is no mention of leadhillite in the Tsumeb-specific literature by authors such as Klein (1938), Burg (1942), Strunz et al. (1958a) and Geier (1961, 1973/74).

The earliest mention of leadhillite in the Tsumeb-related literature appears to be by Medenbach and Schmetzer (1975), with their detailed description of the (now) well-known lead silicate paragenesis (alamosite, melanotekite etc.) that occurred in association with a large (8 cm) leadhillite crystal from the second oxidation zone.

Bartelke (1976) described leadhillite as a rare mineral at Tsumeb citing the description of Medenbach and Schmetzer (1975).

Pinch and Wilson (1977) noted that:

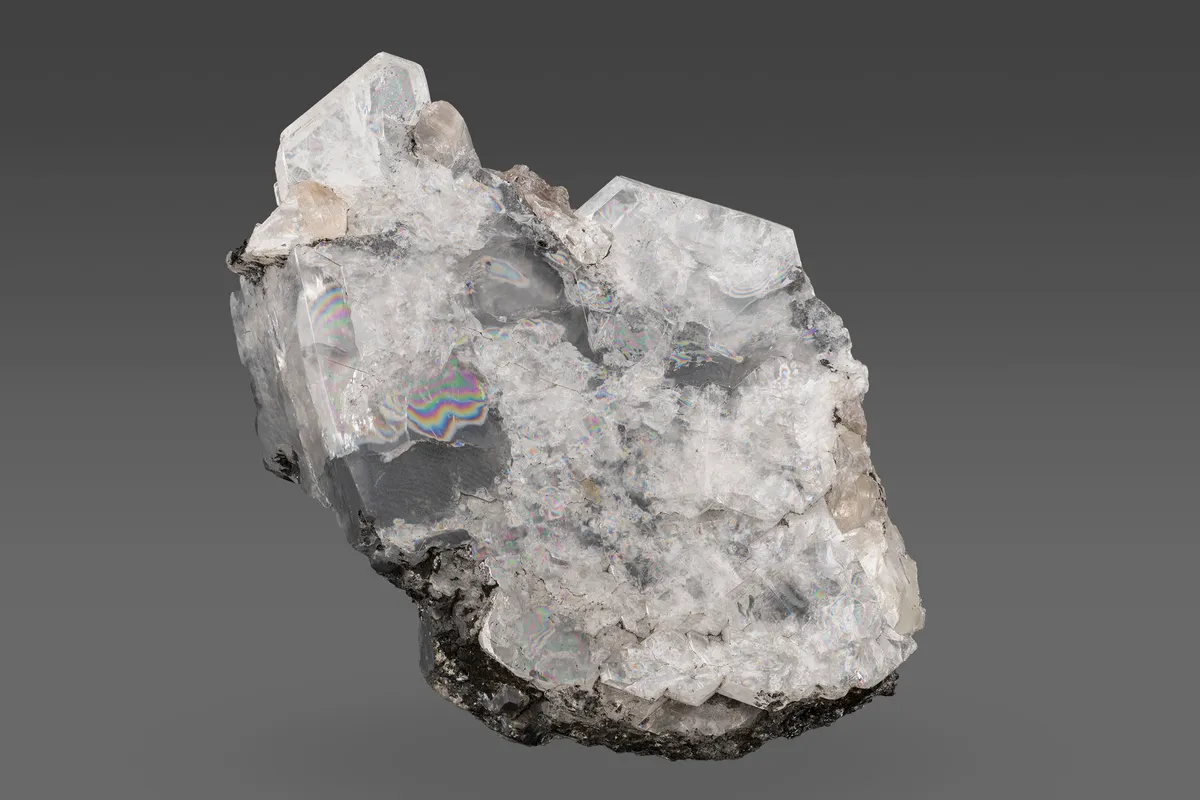

"Leadhillite crystals from Tsumeb are the largest and finest known. They range in habit from small and poorly formed to superb pseudohexagonal tablets and pyramids as large as 13 cm, and weighing several kg. The colour ranges from white to dark gray and pale yellow. Its softness and micaceous cleavage with pearly luster on the cleavage face are diagnostic. It is most common in the lower [second] oxidation zone where it has been found with melanotekite, anglesite, cerussite and alamosite."

Keller (1977a) placed leadhillite in the following "rare mineral paragenesis":

R1: primary sulphides >> wulfenite >> alamosite >> kegelite >> leadhillite >> cerussite.

Keller and Bartelke (1982; page 146, "Sequence R/1") expanded this sequence to include cerussite, larsenite, mimetite, plumbotsumite and willemite.

Keller (1984) observed that leadhillite crystals are often encrusted with a layer of fine cerussite crystals, formed under higher pH conditions.

Gebhard (1999) noted the occurrence of a 4 cm leadhillite crystal of gem quality, formerly in the collection of the late John F. Barlow.

Bowell and Clifford (2014) noted that: "

Tsumeb has supplied the largest leadhillite crystals known – generally an order of magnitude larger than any other locality. … The largest specimen consists of a series of hexagonal prisms spanning 13 cm and weighing in at a staggering 4 kilograms…".

Currier (2015) described the purchase of three outstanding leadhillite specimens during a visit to Tsumeb in 1979; the local dealer parted with them cheaply, in the mistaken belief that they were anglesite crystals.

A 90 mm crystal of leadhillite in the Harvard University Collection (MGMH 107992) is catalogued from 29 Level.

Associated Minerals

alamosite; anglesite; beaverite-(Cu); cerussite; fleischerite; galena; hematite; kaolinite; kegelite; larsenite; macphersonite (?); mathewrogersite; melanotekite; mimetite; plumbotsumite; quartz; queitite; susannite; willemite; wulfenite

Pseudomorphs

The following minerals are reported to form pseudomorphs after leadhillite: cerussite (rare, usually surface alteration only).